For 135 years psychologists have known the secret to how to study effectively. Despite this knowledge being freely available 1,2, most students today still use substandard studying methods 3, as if a century’s worth of research in psychology never existed.

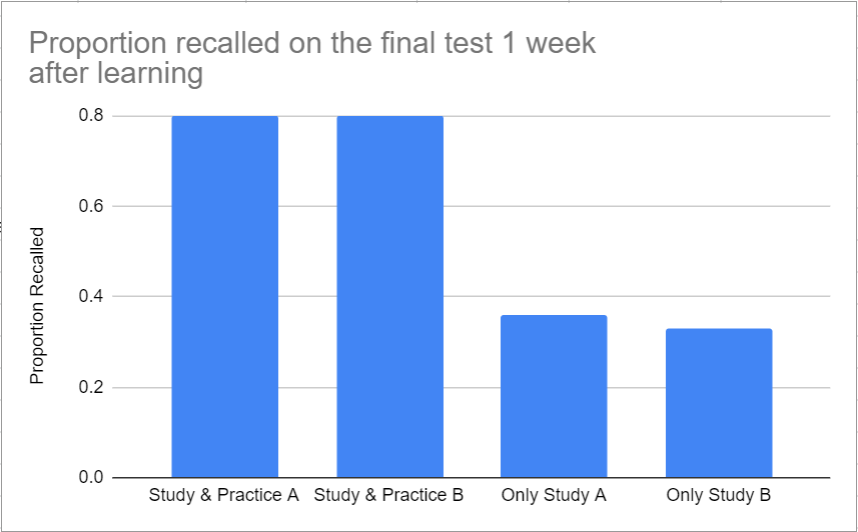

A 2008 study showed that this seems to be so because students think that all methods are similarly effective4. Regardless of the study method, students thought they would remember half the word pairs. However, the results differed massively:

But what are the right studying methods exactly?

In this article you will learn:

- How to stop fooling yourself

- How to study smarter than 99% of students

- The 3-R Method

- How to save time

- Is music part of an optimal studying environment

How Not to Fool Yourself

“The first principle is that you must not fool yourself — and you are the easiest person to fool.”

Richard P. Feynman(5) Nobel prize winning physicist

Years ago when I was studying computer science I took a low-level programming class. I remember reading the study materials and thinking: “this makes sense, I understand this.” However, when I took the exam I failed completely.

True learning requires us to confront our shortcomings. But my method for studying was just re-reading. Which lacks the testing required for deep understanding. Flashcards, because of how they work, do not let that happen. They tell you exactly how smart you are and tell you when you are being a fool.

Make your own physical flashcards

Because you develop a deeper understanding when you take the time to write physically. Multiple studies show this (10)(11)(12).

But an alternative is the software Anki.

Anki is great because it is easy to use, flexible, and allows synchronization across all your devices. You can construct a deck of flashcards on your laptop or desktop computer, and study on your smartphone while waiting for an appointment.

You can also do it in your web browser if you don’t feel like installing the software. However, the software allows you to include audio, pictures, or complicated math formulas.

Paraphrase, never take notes verbatim

It is suggested that if you want the benefits of writing physically while using Anki, you should simply avoid taking notes verbatim but paraphrasing into your own words.

How to Study Smarter Than 99% of Students

In 2009, Karpicke, Butler, and Roediger III found that 83% of students reported re-reading as one of their study methods and that for 54% of students it was their number one strategy. But we know now that re-reading is the inferior way to learn(3). True understanding requires you to test yourself.

In the same study, the researchers found that only 1% of students used retrieval practice ( or practice testing) as their primary method of learning. This means only 1% of students tested themselves with tools such as flashcards.

So, you might have already guessed. The easy way to study smarter than 99% of people is simply to use the best method.

How to Get More Out of Practice Testing

The more time you spend thoughtfully crafting each detail of your summary the better you understand and remember it. In 2011 Bednall and Kehoe investigated the relationship between the quality of summaries students produced and the scores on their subsequent tests and found that as students who took more care with their notes got better results(13).

Why does paraphrasing into your own words work

Firstly, it avoids the first problem of lying to ourselves about how well we understand something. Secondly, when we paraphrase into our own words then we reconstruct knowledge, instead of simply recalling it.

Reconstructing knowledge binds the information in a way that uniquely makes sense to us. Hence the old proverb if you want to remember something explain it.

Spaced repetition aka stop cramming on the eve before the exam

If you have ever tried cramming on the last evening before an exam you know why. It’s harder to distinguish between what you’re learning and the added pressure of needing to understand makes it near impossible.

Study a little every day and space it out over a long time. Anki, the flashcard program, helps you with this. It will test you multiple times over a period of time according to how well you remember your card.

Use the 3-R Method(6)

Read with purpose. Before you start reading a piece of text think about what you want to get from it. What questions do you want to be answered? Having a purpose helps you focus on the most important information which helps you retain it.

Recite and write it down. Writing forces you to actually put down in your own words what you know. Which is different from only thinking that you know something. Writing down, and rephrasing helps you avoid metacognitive errors. Try to be as particular and as detailed as you can. This further helps you form stronger and more useful memories.

Review and act on it. Now look at your source material and your notes. Did you write down everything important? If you didn’t that simply means that the method is working. You are now seeing the facts and the details that you missed or didn’t remember properly. You would not see these facts and these details if you had simply re-read the text.

Studying the Right Way Looks Like a Lot of Work

It does not necessarily have to be. A study by Dickinson & O’Connel (1990), found that the time spent studying between students who did it thoughtfully (like the 3-R method above) and those who used more superficial means of studying, like re-reading, was the same. What differed was the quality of studying and the subsequent grades they got(7).

You also need to remember that there is a cumulative effect on better study habits. Less revisiting of old concepts since you will understand and remember more.

Should You Listen to Music While Learning

The short answer is no. Memory research shows us that your environment when studying is an important factor. It is more important to have a deep understanding of your subject, but for optimal performance during an exam, it is recommended to mimic studying conditions. Basically, if your exam is in silence, then you should also study in silence.

In 1975, psychologists Godden and Baddeley investigated how the environment influenced memory. They used divers, who learned a set of 2 or 3-syllable words and who recalled those words in and out of the ocean. What they found was that divers who remained in their studying environment performed better than divers who switched into or out of the ocean(14).

This means if you study with music you should get better results when taking the exam with the same music. But in most cases, you can not listen to music while taking your exam. So it’s better to imitate exam conditions while studying. But furthermore, some studies show that music harms your performance on tests or exams(8)(15). Although positive results exist too. It seems wiser to err on the side of studying in silence. Perhaps you should practice with ear muffs.

The Bottom Line

Create flashcards with your own phrasing. The more specific the better. Control your understanding and your actual memory with flashcards.

Space out your studying. A bit every day, rather than cramming days before the exam. There is joy in being able to take that time and really understand. Use Spaced repetition programs like Anki for long-term results.

Summary of tips:

- Read once, recall and question.

- Flashcards repeat what you remember

- Connect to what you already know

- Visualize it, draw it

- Don’t cram, space it out

- Try different mediums

- Growth mindset

- Study breaks

- Do something fun at the end

- Dedicated study area

- Active learning

- Study groups

- Sleep well

- Take notes

- Explain

- SQR3 Method: Survey, Question, Read, Recite, Review

- Memorize facts with acronyms, coin sayings, make interactive images, and mnemonics)

- Practice test

- Listen to music before you study

- Keep your blood sugar low

- Create your own flashcards

| Method | Description | Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Elaborative interrogation | Generating an explanation for why an explicitly stated fact or concept is true. | Moderate |

| Self-explanation | Explaining how new information is related to known information, or explaining steps taken during problem-solving. | Moderate |

| Summarization | Writing summaries (of various lengths) of to-be-learned texts. | Low |

| Highlighting | Marking potentially important portions of to-be-learned materials while reading. | Low |

| The keyword mnemonic Low | Using keywords and mental imagery to associate verbal materials. | Low |

| Imagery use for text learning Low | Attempting to form mental images of text materials while reading or listening. | Low |

| Rereading Low | Restudying text material again after an initial reading. | Low |

| Practice testing High | Self-testing or taking practice tests over to-be-learned material. | High |

| Distributed practice High | Implementing a schedule of practice that spreads out study activities over time. | High |

| Interleaved practice Moderate | A schedule of practice that mixes different kinds of problems, or a schedule of study that mixes different kinds of material, within a single study session. | Moderate |

References

- Abott, E. E. (1909). On the analysis of the factor of recall in the learning process. The Psychological Review: Monograph Supplements, 11(1), 159–177. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0093018

- Ebbinghaus, H. (1913). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology. (H. A. Ruger & C. E. Bussenius, Trans.). Teachers College Press. https://doi.org/10.1037/10011-000

- Karpicke, J. D., Butler, A. C., & Roediger, H. L. III. (2009). Metacognitive strategies in student learning: Do students practise retrieval when they study on their own? Memory, 17(4), 471–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210802647009

- Karpicke, J. D., & Roediger, H. L. III. (2008). The critical importance of retrieval for learning. Science, 319(5865), 966–968. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1152408

- Feynman, R. P. (1974). Cargo cult science. Engineering and Science, 37(7), 10-13. https://resolver.caltech.edu/CaltechES:37.7.CargoCult

- McDaniel, M. A., Howard, D. C., & Einstein, G. O. (2009). The read-recite-review study strategy: Effective and portable. Psychological Science, 20(4), 516–522. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02325.x

- Dickinson, D. J., & O’Connell, D. Q. (1990). Effect of quality and quantity of study on student grades. The Journal of Educational Research, 83(4), 227–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.1990.10885960

- Lehmann, J. A., & Seufert, T. (2017). The influence of background music on learning in the light of different theoretical perspectives and the role of working memory capacity. Frontiers in psychology, 8, 1902.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01902 - Perham N., Currie H. (2014). Does listening to preferred music improve reading comprehension performance? Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 28 279–284. 10.1002/acp.2994 https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.2994

- Smoker, T. J., Murphy, C. E., & Rockwell, A. K. (2009, October). Comparing memory for handwriting versus typing. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting (Vol. 53, No. 22, pp. 1744-1747). Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.1177/154193120905302218

- Aragón-Mendizábal, E., Delgado-Casas, C., Navarro-Guzmán, J. I., Menacho-Jiménez, I., & Romero-Oliva, M. F. (2016). A comparative study of handwriting and computer typing in note-taking by university students. Comunicar. Media Education Research Journal, 24(2). https://doi.org/10.3916/C48-2016-10

- Mueller, P. A., & Oppenheimer, D. M. (2014). The pen is mightier than the keyboard: Advantages of longhand over laptop note taking. Psychological science, 25(6), 1159-1168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614524581

- Bednall, T. C., & James Kehoe, E. (2011). Effects of self-regulatory instructional aids on self-directed study. Instructional Science, 39(2), 205–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-009-9125-6

- Godden, D. R. & Baddeley, A. D. (1975). Context‐dependent memory in two natural environments: On land and underwater. British Journal of Psychology, 66(3), 325–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1975.tb01468.x

- Gurung, R. A. R. (2005). How Do Students Really Study (and Does It Matter)? Teaching of Psychology, 32(4), 239–241.

https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2005-13307-006